“Since the mid-20th century, mental illness has become a leading cause of health burden, particularly among adolescents and emerging adults, with most disorders emerging before the age of 25.1“

his quote from an internationally known Australian research team describes the global situation. The recent tragedy in our town has shown that Marblehead is not an outlier to this reality. The burden of youth mental health is heavy here today too.

We have all been aware that mental health has reached a crisis level for some time, but our actual commitment to respond to it has been relatively limited. Part of the problem is the stigma that goes with mental illness – especially for the young. Even when faced with hard facts, many parents and families want to believe these behaviors are just “part of growing up”. The kids will just outgrow them. “I was a bit wild when I was young, too, and I am fine now. I am not worried” In addition, the traditional view is that since chronic illnesses increase with age and therefore more of the limited resources available for chronic illnesses should go primarily to seniors and not wasted on the impulsive kids who don’t really need it as much. And besides, kids don’t vote so politicians don’t pay as much attention to them as they do to seniors. Two recent publications appear to challenge that conventional thinking and make strong economic arguments for increasing mental health services in our communities – especially for the young.

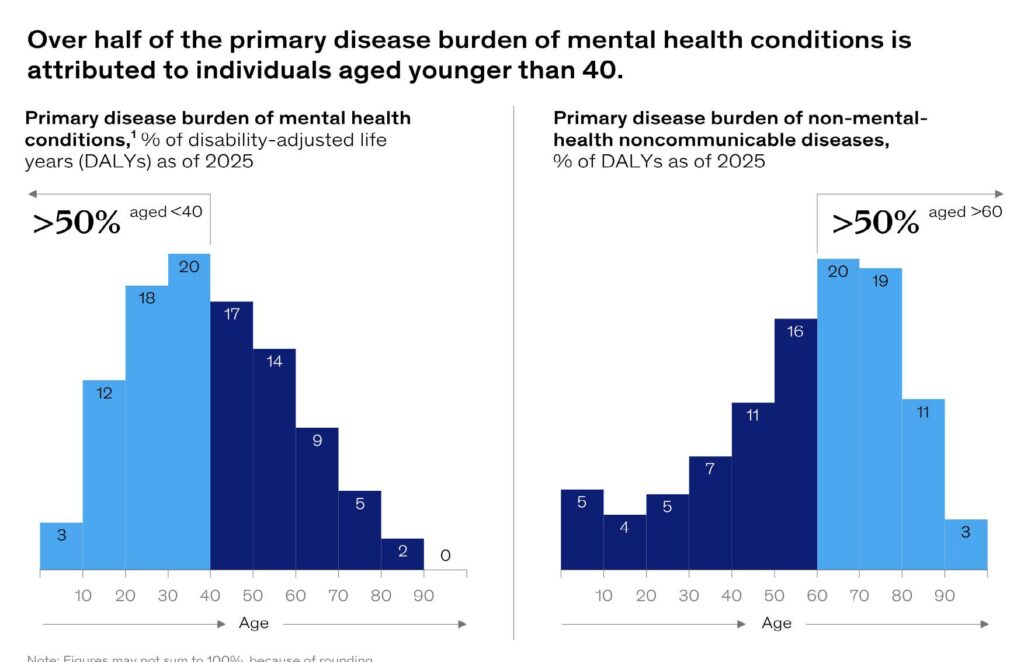

The consulting firm, McKinsey, has looked at mental health from an historical and global perspective2. They recognize that in developed societies because of increased sanitation and anti-biotics, etc., non communicable diseases now cause the loss of more years of healthy life than infectious diseases currently do. Their new data shows that within the non-communicable disease category, mental health conditions now are more costly than diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease and cancer combined. In addition, show that the age of onset of symptoms of mental health is much earlier in life than that of the those from non-mental-health related ones. Figure One compares the age distribution patterns of mental illness with other NCDs. Mental illnesses become prominent well below the age of 40 while other NCDs peak after 60. Intervention in younger individuals allows for positive outcomes to be seen for longer periods. With this background, they argue that significant additional investments in mental health prevention or early treatment could be “transformative” for the global economy. If one treats an individual showing symptoms at age 40 who would otherwise live to 80+ years, the number of healthy years gained is vastly greater than treating person with a non-mental health symptom appearing at 60. Earlier investments in additional mental health care would allow individuals to reclaim years of healthy productive life thereby reducing the direct and indirect mental health disease burden by over 40% and ultimately boost the global GDP by up to $4.4 trillion by 2050. Their most striking conclusion is that every dollar invested in expanding mental health services will generate an economic return of five to six dollars in GDP growth globally.

A second paper focuses entirely on the US. It develops a model which merges psychiatric concepts with macroeconomic theory.3. The psychiatric framework assumes mental illness has three primary destructive components − negative thinking, time loss through rumination, and self-reinforcing behavior. In short, individuals with psychiatric diagnoses are less productive. (Similar destructive behaviors are visible in vulnerable children in schools. Disruptive behavior, lack of attention, chronic absenteeism, etc.)

Their model estimates the annual cost of mental health to the US economy is $282 billion4. The “costs” are consequences of reduced consumption – a health driven financial recession of sorts. They don’t presume to measure pain and/or suffering from mental illness which means they markedly underestimate the real human cost. Their analysis reaches three very significant policy conclusions:

- The most effective investments in mental health occur in treatment of adolescents and young adults. Providing care for everyone ages 16 to 25 would result in $182 Billion in net positive benefits. That is a logical extension of the data in Figure 2. The earlier treatment is provided, the longer the period of healthy behaviors will be maintained in the society and the greater the GDP boost will be from the consumption of these young people who are now unencumbered by mental illness. This suggests that public health partnerships with schools and school districts are critical to maximally reducing long term consequences of mental illness in our country.

- Not surprisingly, expanding the availability of mental health services substantially improves mental health and welfare as well. 122 million Americans are living in mental health professional shortage areas. Eliminating that deficit would show positive benefits of $118 Billion. (Marblehead is not an HRSA mental health professional shortage area.)

- In contrast, reducing the out-of-pocket cost of mental health services. will have minimal impact on improving health status. They hypothesize that individuals with mental illness are less cost conscious than the mainstream population. Their illness keeps them from being logical economic individuals.

Let’s hope that this new thinking can be moved from academic theory to public health practices and school districts here and around the country.

References

“The youth mental health crisis: analysis and solutions”, Patrick McGorry et al, Frontiers of Psychiatry 15 2025

“Investing in the Future: How Better Mental Health Benefits Everyone”, Brad Herbig, Erica Coe and Pooja Talwawadi, McKinsey Health Institute, April 2025

“Macroeconomics of Mental Health”, Boaz Abramson, Job Boerma, and Aleh Tsyvinski, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 32354, April 2024

“Hidden Recession? Mental Illness costs US a staggering $282B annually.” Lindsey Leake, Fortune, May 30, 2024.

• The opinions in this article reflect the author’s alone. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Marblehead Board of Health which he chairs.

The opinions in this article reflect the author’s alone. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Marblehead Board of Health, which he chairs.

Tom Massaro is a Marblehead resident and Chair of the Board of Health.